It’s early on a Saturday morning in late April, and the College of Science Roundtable Advisory Board is gathered in a room at the Inn at Virginia Tech for its semi-annual meeting.

The interim dean is there. Associate and assistant deans are there, along with department heads and chairs. And more than two dozen of the Roundtable board members, who are among the College’s most ardent supporters.

It’s that moment that occurs in every meeting like this when everyone is going around the room introducing themselves. As the introductions move from one to the next, it goes something like this: I graduated from Virginia Tech in 1976...I have two degrees from here...I’m the College’s associate dean of...I have three degrees from here...Two of my children and three of my grandchildren are Hokie grads...

The introduction chain finally comes to a man seated up front, a little off to the side. He pivots his head to look at the bulk of the room:

“I’m Kevin Pitts,” he says, “currently not employed by Virginia Tech, but I hope to be soon.”

Everyone laughs. Everyone already knows who he is. He's Kevin T. Pitts, and though his new “employment” with Virginia Tech had not officially begun, in June he would become the next dean of the College of Science.

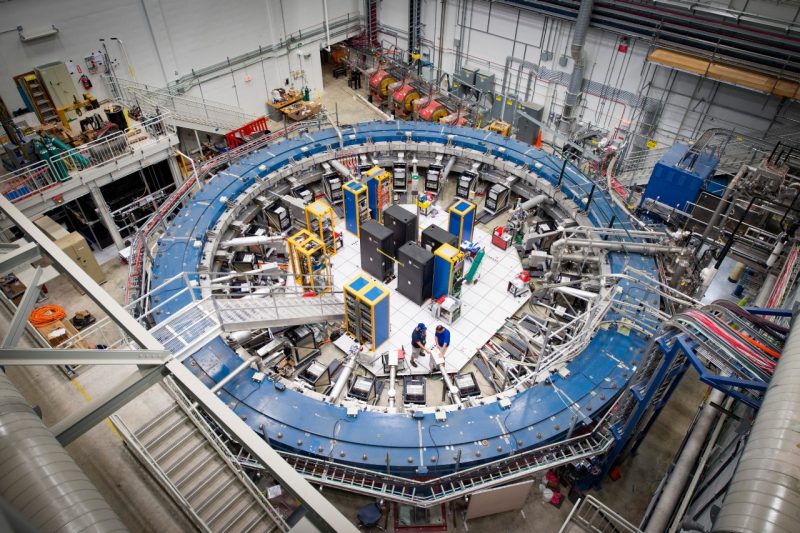

Pitts came to Virginia Tech from the University of Illinois, where he was vice provost for undergraduate education, and prior to that, associate dean for undergraduate education in the College of Engineering. Last year, he became chief research officer at Fermilab, a U.S. Department of Energy facility, where he oversees the lab’s science program, including its multi-billion-dollar international Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment.

He’s known as a high-energy physicist, and at Fermilab was once involved in the discovery of something called the “top quark,” a previously unknown particle that scientists can create by colliding particles in the accelerator. Once mustered into existence, the quark only lasts a trillionth of a trillionth of a second.

It’s the kind of scientific experimentation and discovery that drives Pitts, that after three decades still brings a huge smile to his face.

“For many years, I was just blown away by the fact we could explain how the world works with mathematics,” said Pitts, the Lay Nam Chang Dean’s Chair in the College of Science. “That there were equations that could describe how a particle moves through the air? How the universe works? ‘My gosh, why is that?’ Of course, that’s almost a philosophical question, not a science one.”

Pitts came to physics for what many may think is an unexpected motivation: “You know, we sometimes have this bias that people tend to like things that come easy for them. The thing I loved about physics is that it was really, really hard for me.”

Along that initially trying journey, he realized that the mindset he had developed playing team sports when he was growing up had parallels to the collaborative efforts required among research scientists to explore the unanswered questions of how the physical world works.

Pitts was born, raised, and went to college in Anderson, Indiana, where he played baseball, basketball, and football — for a while. “I took a couple of shots to the head playing football, so I didn’t continue that career.”

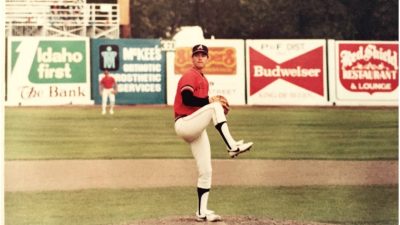

He was forward on the high school basketball team, playing in the state tournament that became well-known around the country from the movie “Hoosiers.” In baseball, he was a left-handed pitcher and continued playing in college, at Anderson University.

“I had this drilled into my head when I grew up playing team sports: team before individual,” Pitts said. “So I was excited to join a discipline within physics where you worked in big collaborations.”

Pitts didn’t begin his scientific career wanting to be a dean. He found the scientific research so enthralling, and his work with students so gratifying that he couldn’t imagine doing something else. He was among University of Illinois teachers listed as “outstanding” by their students for 12 consecutive years.

It’s not hard to imagine that his excitement for the things that science makes possible inspired students.

“I had this drilled into my head when I grew up playing team sports: team before individual.”

—Kevin Pitts

“I tell students all the time, we have learned an amazing amount about nature,” Pitts said. “You can pick any time window and our understanding has grown exponentially, but there are these gigantic questions that we don’t know the answers to, and that's what makes science so exciting.”

When Pitts first came into academia, his mother asked him if he would ever want to be an administrator. She had been a high school teacher, went back to college after Pitts and his brother were grown, got her doctorate, and ultimately became president of the University of Indianapolis.

“I appreciate what you do as an administrator,” Pitts told his mother, “but I’m having too much fun as a teacher and a researcher.”

About 10 years later, Pitts didn’t like the way some of his colleagues in the physics department were guiding students. They were treating students as if they were all going to be teachers or faculty members.

Students were coming to him and saying they loved mathematics and scientific exploration, but they didn’t want to go into academics and they wanted advice on different career options.

Pitts took those issues to the department head, in quite a vocal and persistent fashion.

“And so the department head finally said, ‘Hey, we need somebody to work on these issues at the department level. Why don’t you put your money where your mouth is.’”

That he did. He spent three years working on that and other issues in the department. He learned that he could make a difference in that role too, keeping faculty from getting caught up in the bureaucracy, and working to get them the resources they need to be great teachers, setting up support systems for students.

He was in that role at Illinois when the university learned of a National Science Foundation (NSF) program aimed at improving opportunities for academically talented students who were PELL eligible, Underrepresented Minority, or women to enroll — and graduate — in STEM fields. The universities of Washington and Colorado had pioneered the effort, and the NSF wanted to broaden it.

University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign is in a rural part of the state, yet less than two and a half hours from Chicago, with a public school system in which 86 percent of the students qualify for free or reduced lunches.

“We’d been asking ourselves, what can we do? How can we move the needle? I told the dean, ‘This is what we’ve been looking for,’” Pitts recalled.

The NSF awarded the grant to six universities, including Illinois, where Pitts became the primary investigator. The goal was to bring in a cohort of students and give them extra academic guidance by mapping out a program that would take five years to complete, essentially giving them a “Redshirt” year like in college athletics.

That was the first hurdle, because as Pitts said, “students don’t know a whole lot about college, but they know it takes four years.”

The state of Illinois stepped up with additional funding. Amazon contributed $1 million for scholarships and other support. The university called the program ARISE: Academic Redshirt in Science and Engineering.

They were afraid the students may feel stigmatized, but that wasn’t the case.

“My gosh, it was the opposite,” he said. “Those students would wear their ARISE t-shirts all the time. They were proud to be part of it.”

Now at Virginia Tech, Pitts is cautious to say he won’t promise to transplant that specific program to the College of Science. The College will have to gather its experts, assess what might work, what might not, in a different part of the country.

But you can bet he’ll try something. It’s certainly an area where he wants to use his role of dean to benefit the students and find ways to help talented prospective students who may not have the advantages of others.

“I’d say it this way,” he explained, “I’ve been trained as an experimental scientist, so I understand the role that theory plays. But at the end of the day, we’re going to find out if it works by giving it a try.”

Related Stories

-

Article Item

-

Article Item

-

Redirect Item